# EVM384 – Can we do Fast Crypto in EVM?

Text jointly authored (in reverse alphabetic order) by Paul Dworzanski, Jared Wasinger, Casey Detrio, and Alex Beregszaszi, with help from the entire [Ewasm](https://github.com/ewasm) team.

For feedback there is an [EthMagicians topic](https://ethereum-magicians.org/t/evm384-feedback-and-discussion/4533).

---

[toc]

### Introduction

This is a follow-up from the [original proposal/specification](https://notes.ethereum.org/@axic/evm384-preview), with initial results.

We give a history of crypto in EVM and precompiles. With lessons learned, we prototype an extension to the EVM, called EVM384, which we hope will allow the implementation of fast BLS12-381 operations in EVM. We measure performance. Results show potential for fast BLS12-381 operations in pure EVM384.

The inspiration for this work came from discoveries made while benchmarking various cryptographic algorithms across WebAssembly (Wasm) engines and EVM interpreters, as part of the [Ewasm Benchmarking](https://github.com/ewasm/benchmarking) project.

### History of precompiles

In 2014, the EVM, with [influence from Bitcoin Script](https://web.archive.org/web/20140203145850/http://wiki.ethereum.org/index.php/Ethereum_Script), was designed with 256-bit words and 256-bit arithmetic operations "to facilitate the Keccak-256 hash scheme and elliptic-curve computations" (Yellow Paper, section 9.1).

This early version contained a number of high-level and complex instructions, `SHA3`, `SHA256`, `ECMUL`, `ECSIGN`, `ECRECOVER`, to name a few. They were [subsequently moved](https://github.com/ethereum/yellowpaper/commit/a1ed4cbbcefaa5de9ab3e3ba647a73ac97987472) to form the first set of precompiles, with the exception of `SHA3`, which remained as an opcode, because it was [deemed "more important"](https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/31#issuecomment-159577272) than the others.

The complexity of the EVM was recognised early on and described well in this [blog post](https://blog.ethereum.org/2014/02/03/introducing-ethereum-script-2-0/):

> Too many opcodes – looking at the specification as it appears today, ES1 *[Ethereum Script 1 aka EVM – editor]* now has exactly 50 opcodes – less than the 80 opcodes found in Bitcoin Script, but still far more than the theoretically minimal 4-7 opcodes needed to have a functional Turing-complete scripting language. [...] Other opcodes, however, are excessive, and complex; as an example, consider the current definition of SHA256 or ECVERIFY. With the way the language is designed right now, that is necessary for efficiency; otherwise, one would have to write SHA256 in Ethereum script by hand, which might take many thousands of BASEFEEs *[gas – editor]*. But ideally, there should be some way of eliminating much of the bloat.

In the release of Frontier in 2015, the initial precompiles were secp256k1 signature recovery (ECRECOVER), hash functions (SHA256 and RIPEMD160), and memory copying aka identity (ID) prompted by the cost of copying via `MLOAD`+`MSTORE`.

In early 2016, the first new precompile, [RSAVERIFY](https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/74), was suggested for RSA signature verification. This prompted the proposal of [five precompiles for performing big integer arithmetic](https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/101) as a more generalised option. Some asked for justification for [why it can not be implemented in the EVM](https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/101#issuecomment-216205472). This discussion eventually resulted in the introduction of only one of them, MODEXP, for modular exponentation.

The same year another early suggestion was [BLAKE2B](https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/129). For comparison it included a Solidity implementation, showing the excessive gas requirements, at the time, when the EVM had no bitshifting instructions. Eventually, after much debate and over 3 years later, an alternate version of this precompile was introduced.

Still in 2016, a [SHA1 precompile](https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/issues/180) was proposed for on-chain TLS, SSL, and PGP use-cases. Surprisingly, it was discovered that a reasonably-priced SHA1 can be implemented in EVM. So the precompile for SHA1 was not needed! We can do some hashing in pure EVM!

In 2017, the Byzantium hard fork introduced precompiles for BN128 curve operations (ECADD, ECMUL, and ECPAIRING), and the aforementioned MODEXP.

In 2019, [Weierstrudel was announced](https://medium.com/aztec-protocol/huffing-for-crypto-with-weierstrudel-9c9568c06901) as an implementation of ECMUL in pure EVM. Surprisingly, Weierstrudel has nearly the same gas cost as the ECMUL precompile, and costs much less than multiple ECMULs. Was the ECMUL precompile really needed?

Precompiles became a mechanism to introduce complicated or expensive cryptography into the EVM. But precompile proposal discussions show that they are met with resistance. Adding complexity to a consensus system is controversial. There have been requests to establish a need, and to demonstrate that it can't be done in pure EVM. Successful precompiles have required not only a strong specification, a strong need, and strong evidence that this is a last resort, but also convincing client developers that the precompile is worth the risks and effort. So few precompiles have been accepted, or even proposed.

In the same year, [evmone](https://github.com/ethereum/evmone) was released as a fast EVM implementation. New speed-records were set for every EVM bytecode we benchmarked. As of 2020, some of the principles of the evmone implementation are being considered for adoption by go-ethereum.

With access to much better tooling ([Huff](https://github.com/aztecprotocol/huff), [Yul](https://solidity.readthedocs.io/en/v0.7.0/yul.html)), much faster EVMs (evmone), and successful prior experiments (Weierstrudel, SHA1), we ask the questions: Can pure EVM implementations of ECRECOVER, ECADD, or ECPAIRING have runtime performance competitive with the native precompiles? How about other precompiles? If so, can we deprecate precompiles entirely?

Unfortunately, the answer depends on which crypto. Much of crypto has runtime dominated by bigint arithmetic or bit manipulation for hashing. If we are lucky and have EVM opcodes to match these bottlenecks, then we don't need a precompile. So it may be wise to add new EVM opcodes for crypto primitives, which would increase the scope of fast crypto in pure EVM. These new EVM opcodes should be generic and reusable by different applications.

An example of such a primitive was the the addition of bitshifting opcodes `SHL`, `SHR`, and `SAR`. These made the [performant Blake2b EVM implementation](https://github.com/ewasm/benchmarking/blob/master/evm/input_data/evmcode/blake2b_huff.huff) viable for certain use cases. It had the potential to be useful for a wider set of use cases, [pending on further EVM improvements](https://github.com/ethereum/pm/blob/master/All%20Core%20Devs%20Meetings/Meeting%2062.md#330-eip-2024-proposal-for-supporting-blake2b).

For elliptic curve cryptography, modular multiplication is often the main bottleneck. Most implementations rely on the efficient [Montgomery modular multiplication](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montgomery_modular_multiplication) algorithm. Unfortunate for the elliptic curve use case, the `MULMOD` instruction uses a more generic and expensive algorithm. Introducing support for Montgomery perhaps could cover this bottleneck and expand the usability of the EVM for fast cryptography.

### What about BLS12-381?

Supporting (some) operations on the [BLS12-381](https://electriccoin.co/blog/new-snark-curve/) curve in Ethereum would be beneficial for various use cases, including certain zero-knowledge protocols, as well as better interoperability between Eth1 and Eth2.

Adding a precompile has been proposed in [EIP-1962](https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-1962) and [EIP-2537](https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-2537). It is an open question whether it is feasible to create a performant implementation of BLS12-381 in EVM using opcodes for fast Montgomery arithmetic.

Implementing the BLS12-381 pairing algorithm in EVM is a large project. Luckily, this pairing is available in Wasm through [wasmsnark](https://github.com/iden3/wasmsnark). While Wasm is not EVM, it may be a reasonable approximation of EVM for the purposes of identifying major bottlenecks. Through profiling this wasmsnark code, we identified the bottlenecks, defined a [set of native functions](#Appendix-Bigint-API-for-WebAssembly) for these bottlenecks, and modified both wasmsnark and the [wabt](https://github.com/webassembly/wabt) Wasm interpreter to make use of them.

All measurements are compared to a native Rust [implementation based on EIP-1962](https://github.com/jwasinger/eip1962-bls12-381-bench/blob/dev/src/main.rs). This first experiment will inform and motivate the investigation of fast pairings in EVM384.

----

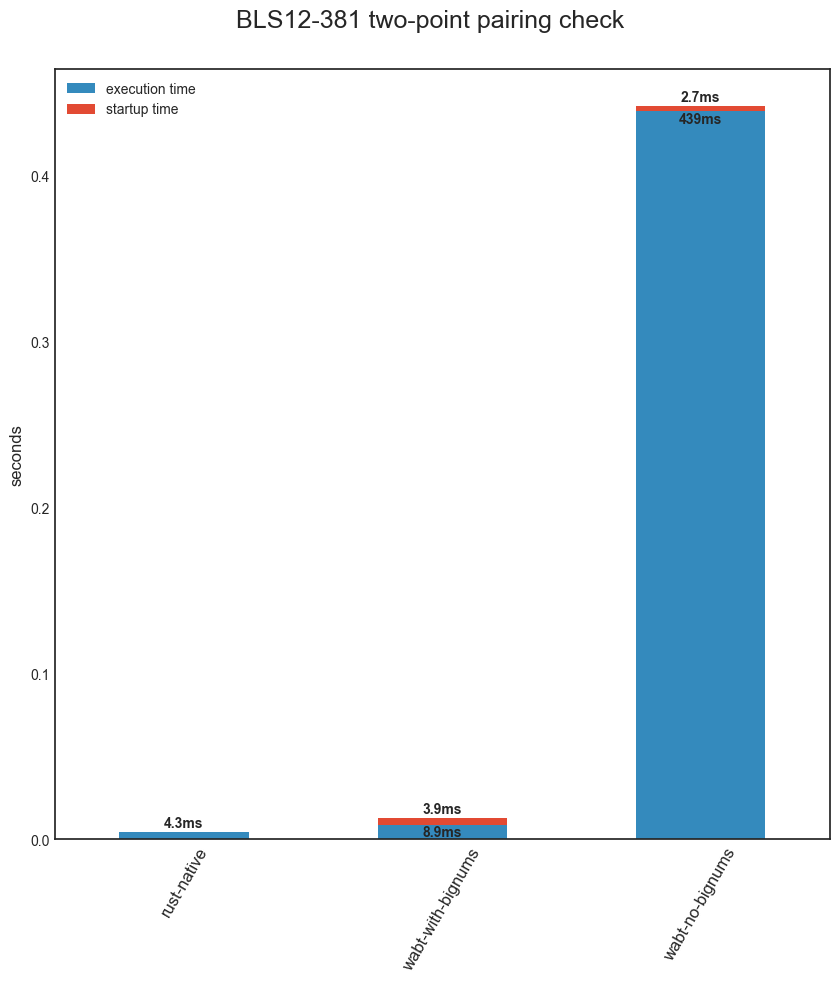

**Figure 1.** Runtimes of BLS12-381 pairing check. Including:

* *rust-native* - the compiled Rust EIP-2537 implementation;

* *wabt-no-bignums* - a Wasm interpreter, Wabt, using code generated by wasmsnark;

* *wabt-with-bignums* - the same interpreter and bytecode, but using calls to native functions for bigint arithmetic.

**Note**: startup time accounts for the parsing and validation of wasm and only occurs once.

----

Results from Figure 1 show that Wasm can perform within 2x overhead of native. This dramatic speedup for an interpreter warrants a similar experiment with EVM.

### EVM384

EVM384 introduces new instructions for the EVM, all of which operate on 384-bit numbers: MULMODMONT384, ADDMOD384, and SUBMOD384. This was previously described in the [original proposal/specification](https://notes.ethereum.org/@axic/evm384-preview). They cover the same three bottlenecks as with Wasm above.

At this time we do not present a final proposal of these instructions, however below are our findings with different variations.

Given the EVM operates on 256-bit stack items, it is not possible to represent 384-bit values in a single stack slot. There are various options with different trade-offs for dealing with this problem. Some possibilities include:

- a) using two stack items for each 384-bit number,

- b) storing each 384-bit number in memory and using memory pointers,

- c) reserving a region in memory, treating it as a stack, and using a single memory offset pointing to the top of this stack.

Our decision was partially driven by the need to implement BLS12-381 using these instructions. To avoid dealing with excessive number of stack items, we opted for prototyping option b).

Our first interface originally clobbered an input with the output. So we made a second version where the output has its own memory offset.

**Interface version 1 (evm384-v1)**: output clobbers leftmost input.

```

addmod384(x, y, mod)

opcode: 0xc0

submod384(x, y, mod)

opcode: 0xc1

mulmodmont384(x, y, mod, r_inv)

opcode: 0xc2

```

**Interface version 2 (evm384-v2)**: output has its own offset.

```

addmod384(out, x, y, mod)

opcode: 0xc0

submod384(out, x, y, mod)

opcode: 0xc1

mulmodmont384(out, x, y, mod, r_inv)

opcode: 0xc2

```

Our convention (borrowed from Yul) is that the leftmost argument is the top of the stack. Each argument is a memory offset, except `r_inv` which is a 64-bit integer on the stack. Both `mod` and `r_inv` are curve-specific constants. These instructions will read 48-bytes from memory offsets at `x` and `y` and store a 48-byte output at `out`.

Every instruction of the EVM handling memory offsets must also ensure that memory is expanded to the highest offset, and the execution is charged enough gas to do so. We hypothesized the memory checking overhead of these variants is significant, and decided to approximate the stack-only option – variant a) above – by removing the memory expansion check done in the instructions of evm384-v2. We call this version **evm384-v3**.

We implemented these versions in [evmone](https://github.com/ethereum/evmone), and [Solidity](https://github.com/ethereum/solidity) to allow for compilation of Yul and inline assembly with these instructions:

- [evmone-evm384-v1](https://github.com/ethereum/evmone/tree/v0.5.0-evm384-v1)

- [evmone-evm384-v2](https://github.com/ethereum/evmone/tree/v0.5.0-evm384-v2)

- [evmone-evm384-v3](https://github.com/ethereum/evmone/tree/v0.5.0-evm384-v2-unsafe)

- [solidity-evm384-v1](https://github.com/ethereum/solidity/tree/evm384)

- [solidity-evm384-v2](https://github.com/ethereum/solidity/tree/evm384-v2) (this can be used for both evm384-v2 and evm384-v3)

### The synthetic loop

Implementing and optimizing the BLS12-381 pairing operation in pure EVM384 bytecode is a difficult task for anyone not well versed in implementing efficient elliptic curve cryptography.

Instead, we developed and implemented a simpler "synthetic" pairing algorithm which in our opinion is an approximation of the actual pairing algorithm (see the [appendix](#Appendix-Synthetic-Loop-Algorithm) for a definition).

Because we use approximations, we first compare the runtime of the synthetic pairing and the actual pairing algorithm, both generated using wasmsnark.

----

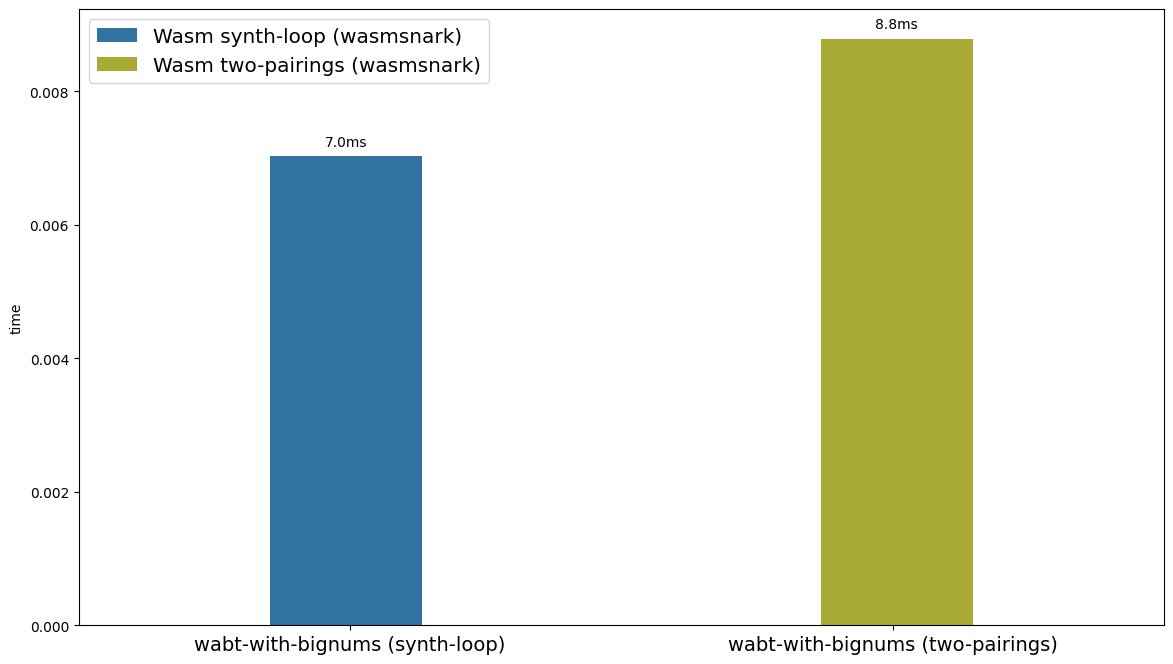

**Figure 2.** Comparison of BLS12-381 pairing runtime with the synthetic loop. Both bytecodes were generated by wasmsnark and executed in wabt with bigint host functions.

----

In Figure 2, our synthetic algorithm reasonably approximates the actual pairing runtime. But the error is non-negligible. We will use `wasmsnark_pairing_runtime / wasm_synthetic_pairing_runtime ~= 1.25` as an `adjustment_factor`. Later we need to apply this `adjustment_factor` to the numbers produced on EVM384 for a fair comparison with native and Wasm.

Next, we implement the same synthetic loop algorithm in EVM384. This gives us a good opportunity to compare our three EVM384 interfaces above. Our choice of language was Yul for its simplicity and closeness to the EVM. We have considered experimenting with the [vast number of Yul optimizer settings](https://solidity.readthedocs.io/en/v0.6.8/yul.html#yul-optimizer) of Solidity 0.6.8, but due to time constraints only used the standard set of optimizations. There is plenty of room to improve both the Yul source code and to find an appropriate set of optimizations.

----

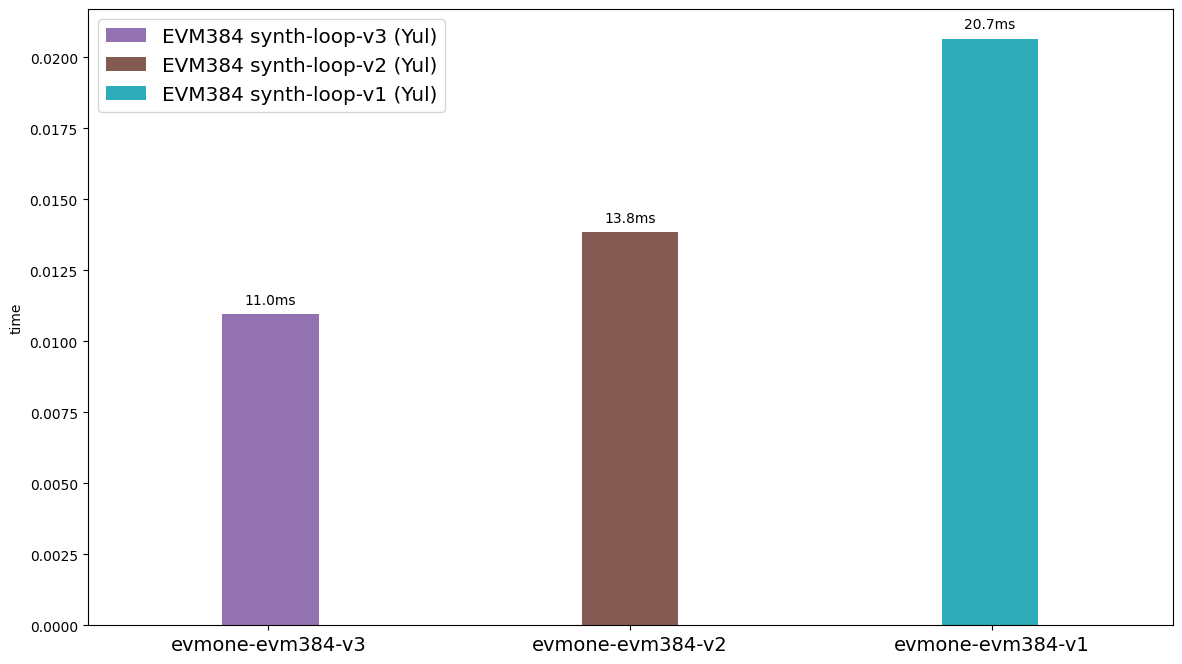

**Figure 3.** Runtimes of the synthetic loop on the different versions of EVM384 described above.

----

Figure 3 confirms our expectations about the different EVM384 versions. In evm384-v1, the clobbering of the output requires extra memory copying, causing a slowdown. In evm384-v2, the overhead of memory checking and expansion is significant. With evm384-v3 this bottleneck of memory checking is removed, resulting in the shortest runtimes.

### Summarizing the results

We compare native, Wasm, and the fastest EVM benchmark from above.

----

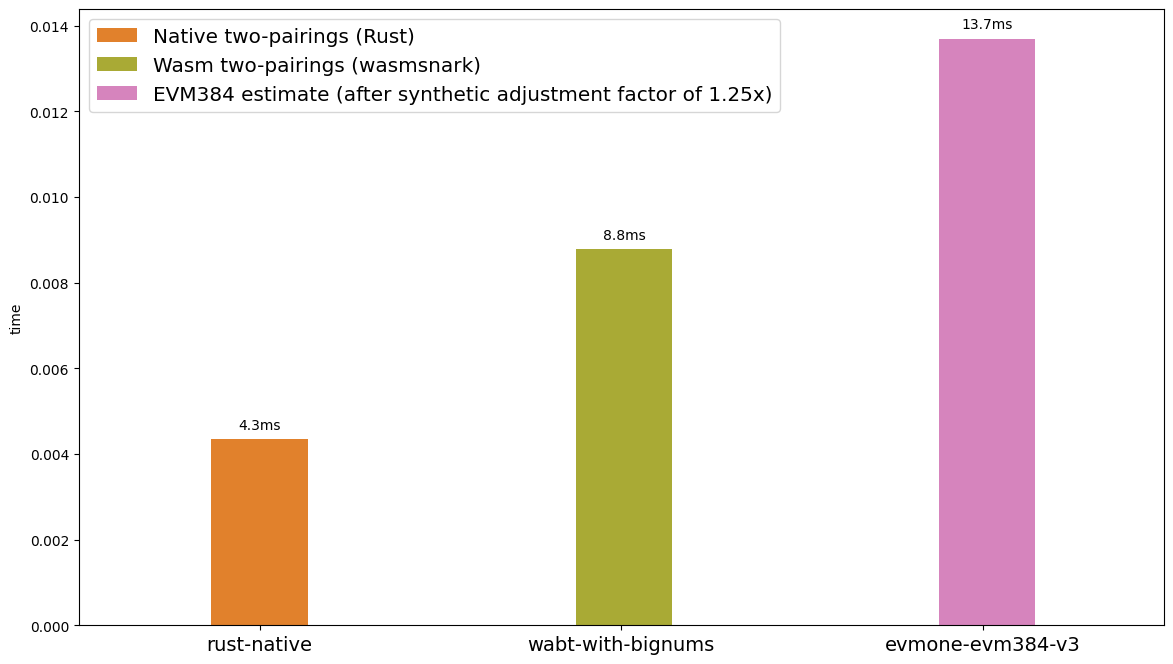

**Figure 4.** Runtimes from pairings in Rust from Figure 1, pairings in Wasm from Figure 2, and the fastest EVM synthetic loop from Figure 3 after applying the `adjustment_factor` computed from Figure 2.

----

From Figure 4, our Wasm implementation is 2 times slower than native and our evmone approximation is 3 times slower than native. Keep in mind that these numbers are a first attempt, and there is a capacity to improve. But the goal of this experiment was to show the feasibility, and motivate the large effort of optimization, an iterative process.

### Conclusion

While this work is not complete, we believe our experiment shows a great potential for extending the EVM with primitives. This approach can be an alternative to the slow process of introducing precompiles.

In its current form, EVM384 would already enable the implementation of various BLS12-curves (BLS12-381 as discussed above, and BLS12-377 proposed by [EIP-1962](https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-1962) and [EIP-2539](https://github.com/ethereum/EIPs/pull/2539)). The primitivity of EVM384 also allows domain-specific optimizations, e.g. for specific curves, or specific operations on some curves. With a precompile the algorithm (including any optimizations) is decided at the time of its introduction, and improving them requires consensus.

As evidenced by the past couple of years, elliptic curve cryptography is a rapidly evolving space. Despite BLS12-381 being a comparatively young curve, first described in 2017, it is already gaining large traction. Many of the zero knowledge systems currently in operation are using the BN128 curve, added to Ethereum in 2017. Only in the short span of 3 years, many new zero knowledge systems are keen on using BLS12-381. It is prudent to expect new, and better, curves will be devised in the coming years, and we should not want to introduce specific precompiles for each of them. In our opinion, EVM384 could serve as a template for EVM512, EVM768, etc. covering many systems in the future.

As shown with the different EVM384 variants, small and straightforward optimisations can manifest in large gains. We see potential for reducing the performance gap even more, compared to WebAssembly and native.

For best results, a collaboration between experts with background in cryptography, EVM, and various optimization techniques would be beneficial. This involves exploring different algorithms for the desired curve operations; different EVM384 interfaces, including the fully stack-based option and perhaps new instructions; potentially trying out other languages besides Yul.

As a next step we suggest a working implementation of BLS12-381 pairing and multiexponentiation (those defined as `BLS12_PAIRING`, `BLS12_G1MULTIEXP`, and `BLS12_G2MULTIEXP` in [EIP-2537](https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-2537)) to be implemented. This would allow for experimenting and finding an appropriate EVM384 interface, and serve as a basis for a candidate EIP.

Our team would be open to collaboration with interested parties.

### Future work ideas

Some potential improvements we came across include:

- **MULMODMONT384 optimizations:** A slightly less generic [mulmodmont limited to 383-bits](https://hackmd.io/@zkteam/modular_multiplication) gives a ~10% speedup over the current version.

- **Split primitives:** We can explore breaking **MULMODMONT384** into opcodes for **MONTREDUCE384** and **MUL384**, which alows supranational's [bls12-381 optimization](https://github.com/supranational/blst/blob/master/src/fp12_tower.c#L21-L25) giving a ~10% speedup.

- **Fused primitives:** Analogous to fused multiply-add, we can similarly fuse primitives to reduce the number of executed opcodes. We can take this far by fusing many operations together, like an opcode for `f6m_mul` in wasmsnark. But these fused primitives are less generic.

### Notes

The above work was conducted as part of the [Ewasm benchmarking project](https://github.com/ewasm/benchmarking). This benchmarking framework was used to generate the results on an Azure VM (Standard D4s v3, 4 x Intel Xeon E5-2673 @ 2.30GHz, 16 GiB memory) and can be reproduced using the instructions found within.

### Appendix: Synthetic Loop Algorithm

The synthetic loop was designed to approximate the workload of an actual BLS12-381 pairing, while being easy to implement. A profile of the two-pairing benchmark on wasmsnark to count the number of calls to the three primary bignum host functions showed 23678 calls to `f1m_mul`, 75565 calls to `f1m_add`, and 35891 calls to `f1m_sub`.

To find an algorithm that would be easy to implement, we looked for a relatively simple function in wasmsnark that is used in the pairing computation, and found`f6m_mul`. A profile of `f6m_mul` showed 18 calls to `f1m_mul`, 50 calls to `f1m_add`, and 20 calls to `f1m_sub`. These profiles show that the proportion of calls to the three bignum host functions for `f6m_mul` (20%, 57%, 23%) is close to the proportion of calls in the two-pairing benchmark (17%, 56%, 26%).

The synthetic loop is simply a loop that calls `f6m_mul` 1350 times, so that the number of calls to the bignum host function `f1m_mul` in the synthetic loop (`18*1350 = 24300`) exceeds the number in the two-pairing benchmark (23678).

For reference the synthetic loop is implemented in [Wasm](https://github.com/ewasm/scout.ts/blob/f6m_mul_loop-standalone/assembly/bls12-pairing/main.ts#L3-L69) and [Yul on EVM384](https://github.com/ewasm/evm384_f6m_mul/blob/master/src/v2/benchmark.yul#L468-L483).

### Appendix: Bigint API for WebAssembly

We introduce three host functions under the `env` namespace:

- `bignum_f1m_add(x:i32, y:i32, ret:i32)` (~= `ADDMOD384`)

- `bignum_f1m_sub(x:i32, y:i32, ret:i32)` (~= `SUBMOD384`)

- `bignum_f1m_mul(x:i32, y:i32, ret:i32)` (~= `MULMODMONT384`)

Every argument listed is a 32-bit memory offset, and none of the functions return a value. The memory offsets are expected to contain 48-bytes (384-bits) in little endian order.

This interface is very similar to evm384-v2, with the exception of `bignum_f1m_mul` has `mod` and `r_inv` values hardcoded for the BLS12-381 curve.

Note that the two-pairing wasmsnark benchmark uses four additional host functions (`bignum_int_add`, `bignum_int_sub`, `bignum_int_mul`, `bignum_int_div`). These four host functions give a small but non-negligible speedup when used in addition to the three host functions above. But for the purposes of comparison to EVM, these additional integer host functions are not as relevant because operations on EVM already operate using 256-bit widths versus 64-bit widths on wasm.