# EVM384 -- Update on the interface

Text jointly authored (in reverse alphabetic order) by Paul Dworzanski, Jared Wasinger, with help from the entire [Ewasm](https://github.com/ewasm) team.

For feedback there is an [EthMagicians topic](https://ethereum-magicians.org/t/evm384-feedback-and-discussion/4533).

---

[toc]

## Introduction

This is a follow-up on our previous document: [EVM384 – Can we do Fast Crypto in EVM?](https://notes.ethereum.org/@axic/evm384)

In this update, we continue our investigation into adding EVM opcodes `addmod384`, `submod384`, and `mulmodmont384`, which we call EVM384 opcodes.

Before implementing large cryptographic algorithms with these opcodes, we first experiment on a smaller algorithm, with different languages, and with different interfaces to EVM384 opcodes. We would not want to implement large cryptographic algorithms only to have to rewrite them in a more a optimal language or with a more optimal interface to opcodes.

## The EVM384 Interface Candidates v1 to v7

The most optimal interface is v7. In this section, we discuss the other interfaces which we tried before we arrived at v7. These earlier interfaces can be skipped.

For a complete specification of each interface, see the [EVM384 specs doc](https://notes.ethereum.org/6K7FEgPWS2S2Tdw2S5NKmQ).

For implementations of these interfaces in evmone, which we use for benchmarking below, see [evmone384v1](https://github.com/ethereum/evmone/tree/v0.5.0-evm384-v1), [evmone384v2](https://github.com/ethereum/evmone/tree/v0.5.0-evm384-v2), [evmone384v3](https://github.com/ethereum/evmone/tree/v0.5.0-evm384-v2-unsafe), [evmone384v4](https://github.com/jwasinger/evmone/tree/evm384-v4) and [evmone384v5](https://github.com/jwasinger/evmone/tree/evm384-v5), [evmone384v6](https://github.com/jwasinger/evmone/tree/evm384-v6), and [evmone384v7](https://github.com/jwasinger/evmone/tree/evm384-v7).

### Interfaces v1, v2, and v3

These first three interfaces were introduced in our previous documents. As a reminder, version 1 is stack-only. Suspecting bottlenecks from stack manipulation in version 1, we designed version 2 which keeps values in memory and passes memory offsets as stack items. Version 3 is like version 2 but the opcodes don't check memory offset overflow in EVM384 opcodes, which is unsafe and useful only to measure memcheck overheads.

### Interface v4 and v5

We suspect that setting stack items for field parameters may be redundant and expensive. With this in mind, we designed interface v4 by modifying v2 to exclude stack items for field parameters. We just hard-coded the field parameters for BLS12-381 -- we assume a way to change these hard-coded field parameters, perhaps with an extra opcode.

We also implement v5, which is v4 modified to unsafely omit memory overflow checks, similarly to v3, to measure memcheck overhead.

### Interface v6

We notice speedups from using fewer stack items in v4 and avoiding memory checks in v5. We design v6 to only use one single stack item in a way which safely avoids most memory checks. We do this with two tricks: virtual registers and packing. Virtual registers are 256 contiguous 48-byte chunks of memory, immediately followed in memory by a 257th register with the fixed field parameters. Our inputs and outputs to EVM384 opcodes are byte-sized indices to these registers packed into a single stack item.

### Interface v7

Because of the awkwardness and limitations of v6's virtual registers, we look for an alternative. To limit the stack manipulation bottleneck, we continue to pack all arguments into a single stack item. In this version, each argument is a 32-bit memory offset. There are four arguments: two offsets to the 48-byte input values, an offset to the 56-byte fixed field parameters, and offset to the 48-byte to put the output. Each EVM384 opcode operates over these four memory offsets.

## Huff vs. Yul

Besides opcode interfaces, we are also interested in languages for optimizing cryptographic algorithms using EVM384 opcodes. We use low-level languages Yul and Huff.

As in our previous doc, we study `f6m_mul`, an expensive part of a pairing algorithm. We implement `f6m_mul` in each language for various versions of EVM384.

* Huff: [v2, v4, v6, and v7](https://gist.github.com/poemm/bf50b9c8f18c33c0883461ede3a4ae8a) (There is no v1 implementation in Huff. But we can use v2 in a v3 engine and v4 in a v5 engine. This is because v2 and v3 share the same interface, and the v2 `f6m_mul` implementation does not overflow memory. Similarly for v4 on the v5 engine.)

* Yul [v1, v2, v3, v4, v5](https://github.com/ewasm/evm384_f6m_mul/tree/master/src) (There is no v6 and v7 implementation in Yul.)

## The Numbers

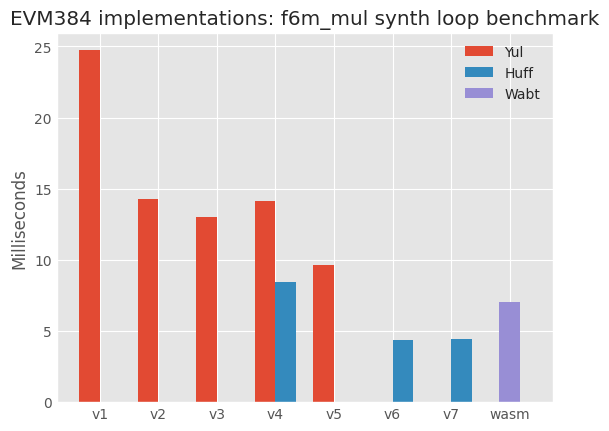

**Figure 1.** Runtimes for the synthetic loop (described in our [previous document](https://notes.ethereum.org/@axic/evm384#The-synthetic-loop)) for `f6m_mul` implemented in EVM384, comparing different interfaces and different languages.

___

Interfaces v6 and v7 are the fastest. This is because they only use a single stack item. The other interfaces use between three and five stack items per EVM384 opcode. Removing this stack overhead gives significant speedups. v7 has more memory checks than v6, but v6 has extra multiplications (`48*idx`) to get memory offsets to the register indices.

As for languages, Huff has a speedup over Yul. But that does not mean that Yul is worse, since some of the tricks used in our Huff code can be ported back to the Yul implementation. With Huff, you are forced to write pure EVM, and look for hand-optimization tricks. A good Yul programmer will think about EVM when writing Yul.

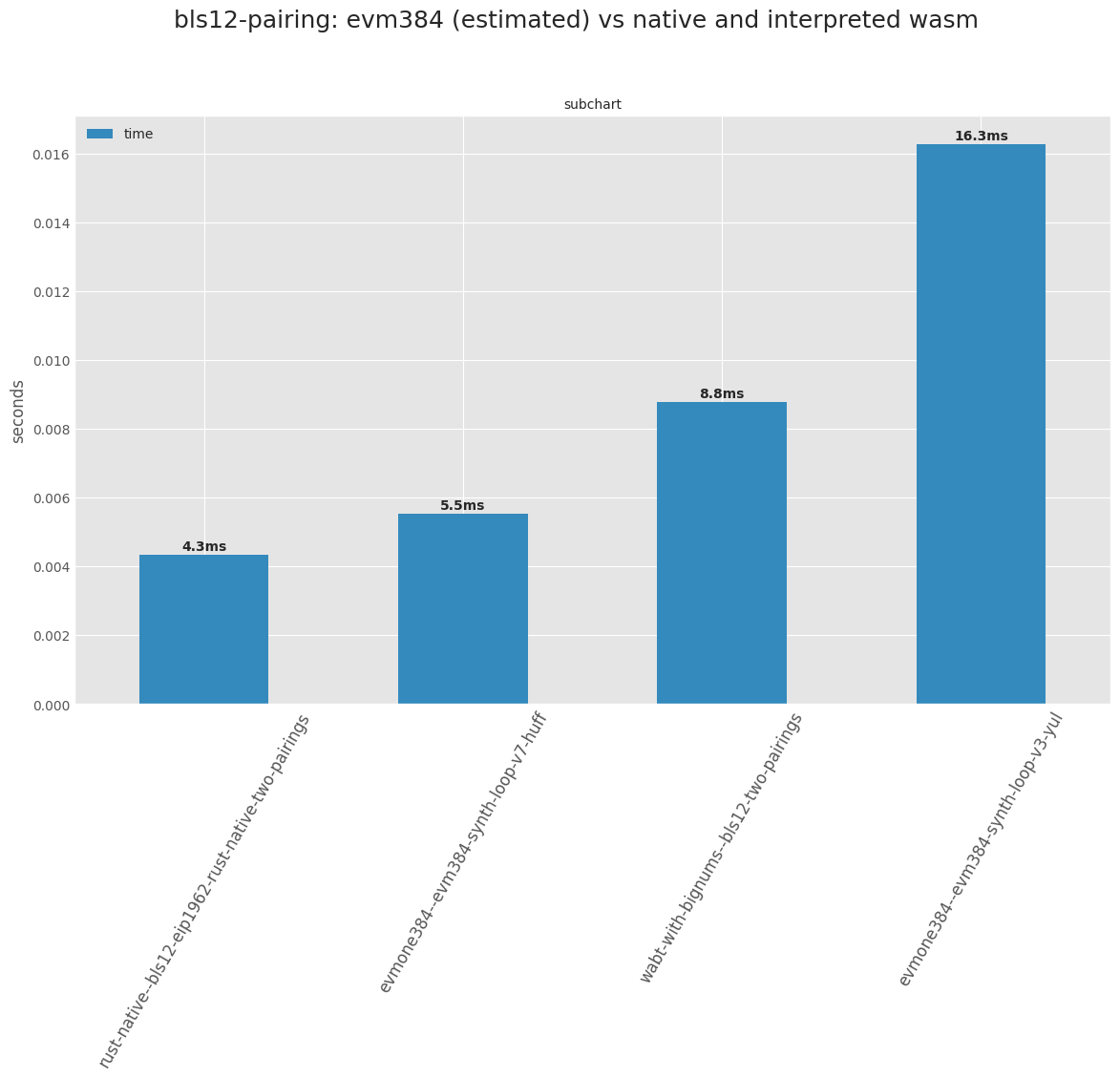

**Figure 2.** Runtimes for pairings in native and wasm, along with our synthetic pairing (synthetic loop corrected with adjustment factor, as described in [our previous document](https://notes.ethereum.org/@axic/evm384#The-synthetic-loop)) in EVM.

---

Surprizingly, interface v7 beats Wasm in the synthetic loop. This is because Wasm has more stack manipulation before calling each bigint function. We think that we can tune the Wasm interface to compete with EVM384 v7. But our goal is EVM384 performance.

There is one caveat. The estimate above is based on an adjustment factor which gives different cost adjustments for different versions, even though we expect the same cost for non-EVM384 parts of the algorithm. So we don't know whether we can acheive this speed for the full pairing algorithm. But the numbers encourage further work nonetheless.

## Conclusion and Next Steps

The v7 runtime gives hope for a baseline EVM384 implementation of the BLS12-381 pairing with under a 2x slowdown from native. The performance gap may be decreased further after open calls for code-golf and implementation optimization.

Not mentioned are considerations for gas cost, in addition to runtime. Using a single stack item interface like v7 is also a good design for minimizing gas cost.

A third consideration is bytecode size. A disadvantage of v7 is larger bytecode size (as compared to v6). The v7 `f6m_mul` bytecode is around 1500 bytes. If bytecode size becomes a problem, we may consider modifying v7 to pack two-byte offsets instead fo four-byte offsets. This would allow using `PUSH8` instead of `PUSH16` to set up the stack for each EVM384 opcode, saving eight bytes per EVM384 instruction. Another way to cope with bytecode size is to put each curve operation into a separate contract to be used as a library.

We discussed another interface which completely removes stack items is to give each EVM384 opcode an immediate with packed offsets like v7. But immediates could break EVM backwards compatibility -- the topic of immediates was discussed multiple times with other EIPs. The v7 interface may allow straghtforward transformation of code to a new version with immediates, so v7 code remains flexible. But we don't think that the savings will be large anyway.

One more note. We use little-endian byte ordering in v7. This is inconsistent with EVM's big-endian convention. We plan to create a new interface version like v7 but using big-endian for all values. This will allow us to measure whether there is significant overhead in reversing the byte ordering for each operation to the common little-endian format expected by most modern computer architectures. If this overhead is insignificant, then we will pivot to a new interface version which is like v7 but big-endian.

What are the next steps? We are settling on interface v7, with the possibility of changing offsets to two-bytes each and using big-endian for values. We are planning to publish an EIP after these two questions are answered. We encourage people to begin planning the implemention of cryptographic algorithms with interface v7, and considering Huff as a language.